Dear Paul,

Some insights into Abelard's philosophy.

Pierre Abélard owes his philosophical importance to the role he played during the

"Querelle des Universaux". The problem of the status of the Universals was indeed one of the crucial questions that medieval philosophers would debate.

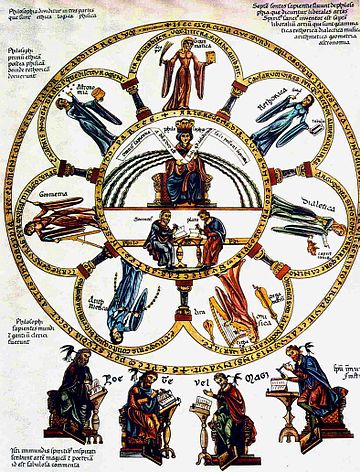

First of all, it is good, I think I should point out that the teaching of philosophy is called the

liberal arts.The liberal arts is a term that refers to the fundamental intellectual disciplines whose knowledge since Hellenistic and Roman antiquity was considered indispensable for the acquisition of high culture.

The liberal arts were grouped into two cycles: the

trivium, the most famous, includes grammar, rhetoric and dialectics, and the

quadrivium, includes all four branches of mathematics (arithmetic, geometry, astronomy and music).

The trivium gives the methodology, the "voces", while the quadrivium gives the content, the "res".

In Christian thought such as the Augustine formula, knowledge of the liberal arts is considered to be the preliminary step in the study of theology based on Holy Scripture, which must be understood and interpreted.

Philosophy is enthroned in the middle of the seven liberal arts

Abelard's philosophy

Abelard's philosophy is based on

Aristotle's reading but only through

Boethius and therefore only knows the logica vetus, the old logic. He also knows

Saint Augustine and the Isagogé of

Porphyry. His thinking is done in the context of Christianity.

Abélard is first and foremost

a logician and brings a new method. A champion of dialectics, he gave Western thought his first Discourse on the method, practising methodical doubt long before Descartes. This method involves a reflection on language.

Abelard is part of an era considered as a medieval golden age or the Renaissance of the 12th century

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Renaissance_of_the_12th_centuryhttps://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Renaissance_du_XIIe_si%C3%A8cle - wikipedia wrote:

- New technological discoveries allowed the development of Gothic architecture

The dispute over the Universals

The dispute over the UniversalsThe question of the Universals is that of

the nature of Ideas. The question had already opposed

Plato and

Aristotle but it should be remembered that in the Middle Ages the texts of Antiquity are in large part lost. In Abelard's time, only the

Timaeus and Aristotle are known as Plato and what is now called the old logic or

logica vetus. Abélard considers a certain corpus from Boethius (4th century).

Boethius translated "Interpretation and Categories". He comments (without translating them) on the other books of the

"Organon".

Abélard therefore ignores Aristotle's" Analytics". He read the

"Isagogé" of Porphyry in which the latter asks the question that will be that of the Universals dispute:

do concepts exist?

If so, what is their nature?

Is the Universal a res (a thing) or a vox (a sound, a word).

Thus medieval thinkers question an issue that was debated in antiquity but ignore ancient solutions and thus take the problem to zero. It should also be noted that this dispute on the Universals must be thought of in the religious context of the time.

Porphyry, in his introduction to the Categories of Aristotle writes:

- Quote :

- "Do species and genera exist in nature as real things or do they only exist as thoughts in our minds. If they exist outside us, are they corporeal or non-bodily? Are they separate from or within sensitive objects? »

Abélard stands in the Conceptualism: There are only singular things and universality is only in words. But the Universals are not nothing, however. This is a fact that is based on divine ideas. The Universals are before man and things like Ideas and constitute the content of the divine spirit. Words are certainly meant to mean something, but they are based on reality. Language is not the veil of reality but its expression. The concept is not arbitrary.

Abélard distinguishes between vox (natural sound) and sermo (meaning of words to which he recognizes universality).

It distinguishes the denominative function from the significant function of an expression.

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/universals-medieval/#UnivAccoAbelArisConcAbélard is the first to use the word "theology" in the current sense of the term. The word was only adopted belatedly by Christians because of its pagan origins.

In Abélard's work, theology became dialectical. It is not only a question of explaining the Scripture of the Bible but also of arguing with reason. In

Sic et non (Yes and No), Abélard gathers a sum of contradictory sentences from the

Bible and the Fathers of the Church. It shows that the authorities' texts must not be adopted without criticism. The method should explain the different opinions and their reasons, evaluate them and, as far as possible, find a solution.

With regard to content,

Abelard's theology refers the terms "Power", "Wisdom" and "Goodness" to the three persons of the Trinity. The Father is in agreement with omnipotence, the Son is in agreement with his wisdom. The Holy Spirit is in agreement with the Grace and Goodness of God. This is how God is three people. Some will accuse him of believing in tritheism (there are three gods), while others will claim that Abelard denies the reality of the three divine persons by reducing their names to simple divine attributes. These two theses are misinterpretations.

He will also apply

a new notion of ethics.

What is important is not so much the act as the intention and the essence of repentance lies in contrition. Thus the external behaviour is, as such, morally indifferent. It is the intention or conviction that counts. Tendencies are not bad or good, but it is acquiescence to something bad that is sinful. Good lies in adhering to God's will, evil in despising it. Intention is therefore the foundation of morality because "Not what is done, but in what spirit it is done, that is what God weighs. »

Abelard's thought has the revolutionary aspect that man takes his place in creation and becomes its centre.

God created the world but man is free to follow the path he chooses.

He can do something other than God worshipped and can even be critical of the Holy Scriptures, which is not tolerated before him.

By refusing close control by the clergy of knowledge and opinion, Abélard goes beyond what the

Gregorian reform (11th century) had more boldness and foreshadows the emancipation that we will see in the

Renaissance.

We are not far from the

- Quote :

- Cogito Ergo Sum

(I think therefore I am) of

Descartes.

He is innovative and opposes all his contemporaries, he initiates a new trend of universalist thought that will be taken up by others and will last until the revolution of the sixteenth century.

His main works:

Theology of the Sovereign Good (1120)

Sic et non (1122)

History of my misfortunes (1132)

Correspondence with Heloise and in particular the rule for the Paraclete (1135-1139)

Ethics or Know Yourself (circa 1139)

Kind regards,