Meles meles

Censura

Posts : 5122

Join date : 2011-12-30

Location : Pyrénées-Orientales, France

|  Subject: Fate, fortune, risk, gambling and probability. Subject: Fate, fortune, risk, gambling and probability.  Thu 21 Apr 2022, 16:07 Thu 21 Apr 2022, 16:07 | |

| Games of chance, such as played with knucklebones, coins and dice, have existed since antiquity and even when there is a large degree of skill involved - such as with the backgammon-like 'Royal Game of Ur' (played with four-pointed tetragonal 'dice'), chess, draughts, card-games, even darts - estimating probability is still key to the tactics of play. However although important in gambling and hence that most vital of human interests - money - the first systematic mathematical analyses of probability were not done until the mid 16th century by the Italian Gerolamo Cardano (that's in in the western world, there is some evidence that Arab and Indian mathematicians had looked into it a little earlier). Cardano was a polymath whose interests ranged through mathematics, medicine, biology, chemistry, astronomy and philosophy, but he was also an inveterate gambler who was always short of cash and who once had to pawn his wife's jewellery to pay his gambling debts. It was his addiction to gambling, whether at cards, dice or backgammon, that drove him to try and understand mathematically what was going on so he could win more often. His book about games of chance, Liber de ludo aleae (Book on Games of Chance), written around 1564 contains the first systematic treatment of probability such as calculating the mathematical chance of throwing a six with a single dice, or throwing two sixes with two dice etc. Moreover he demonstrated that odds could be defined as the ratio of favourable to unfavourable outcomes (which implies that the probability of an event is given by the ratio of favourable outcomes to the total number of possible outcomes). However so concerned was Cardano about keeping this potentially winning knowledge to himself that this pioneering work was not published until 1663. Finally then, nearly a century after his death, Cardano's pioneering work could be read and developed further by other eminent mathematicians, such as De Moivre, Descartes (another avid gambler), Leibnitz and Newton. Fortunes could be won on the throw of a dice, the toss of a coin, or the card played - or lost as Cardano was well aware - yet for centuries up until the seventeenth century, everyone seems to have unquestioningly accepted that it was just unknowable fate that was determining the game's outcome. So why did it take so long for anyone to set about studying mathematical probability? I can think of several possible reasons: - Games of chance were often seen as being a demonstration of the favour of the gods, specifically Fortuna, goddess of luck, or Venus, goddess of prosperity and victory. In ancient Rome when playing the popular game tali (played with four 4-sided rectangular 'dice' usually made from sheep's or goat's knucklebones and each with sides numbered numbered I, III, IV and VI) the throw that beat all others, the one with each bone showing a different number, was called the Venus Throw, by contrast the worst throw possible, four I's, was called the Dog Throw. But if I've worked it out correctly the chance of throwing either the Venus or the Dog was exactly the same, 1:35.

- In this regard introducing a random element into the ritual was often part of the practice of divination to discover the will of the god being appealed to. Rome's auspicious chickens could reveal Jupiter's will according to which direction they wandered off after being released, meanwhile the divination method of casting lots (Cleromancy) was used by the remaining eleven disciples of Jesus in Acts 1:23-26 to select a replacement for Judas Iscariot. So was attempting to understand the mathematics involved seen as interfering with fate or blasphemously trying to understand the mind of god, and so accordingly best avoided?

- There again before wholly unbiased dice the true statistical probability might not be readily apparent even when one discounts the vagaries of natural sheep knucklebones or dice that had been deliberately weighted by tricksters. The emperor Claudius (another keen gambler) wrote a treatise on dice games in which he stated his firm opinion that there was a sort of magical bond between a player and the dice - especially if they were his own personal set - although maybe that was because he knew his own dice to be weighted in a specific way. Even today many gamers superstitiously have their own special rituals when throwing dice, such as blowing on the cup or closing their eyes when they throw, while roulette players often stick to their lucky 'winning numbers' despite the odds of the game always being stacked, just slightly, in favour of the casino and so that in the long run the house always wins.

- Humans, despite being quite good at seeing patterns in sets of data, are actually notoriously poor at correctly estimating probabilities and so perhaps when the mathematical calculation of probability appeared to produce counter-intuitive results they were simply dismissed as being wrong. Many people, having just thrown five heads in a row would still predict the sixth throw to be more likely another head than a tail - despite in reality it being still a 50% chance, assuming a regular coin.

- The basic maths of probability theory are not particularly complicated, illogical, difficult to perform, nor requiring of advanced mathematical techniques, for example it doesn't require an understanding of calculus (developed independently by Newton and Leibnitz in the late 17th century) or of imaginary and complex numbers (discovered by Cardano himself a century earlier). But was its association with gambling perhaps seen as debasing mathematics ("the language of the universe" to use Galileo's expression) or as being unworthy of study by serious mathematicians, until the ideas of the Enlightenment made it acceptable?

Any thoughts then on the history of probability and perhaps how understanding the maths involved might have changed our perception of the world?

Last edited by Meles meles on Thu 21 Apr 2022, 19:42; edited 8 times in total (Reason for editing : typos) |

|

Triceratops

Censura

Posts : 4377

Join date : 2012-01-05

|  Subject: Re: Fate, fortune, risk, gambling and probability. Subject: Re: Fate, fortune, risk, gambling and probability.  Thu 21 Apr 2022, 18:07 Thu 21 Apr 2022, 18:07 | |

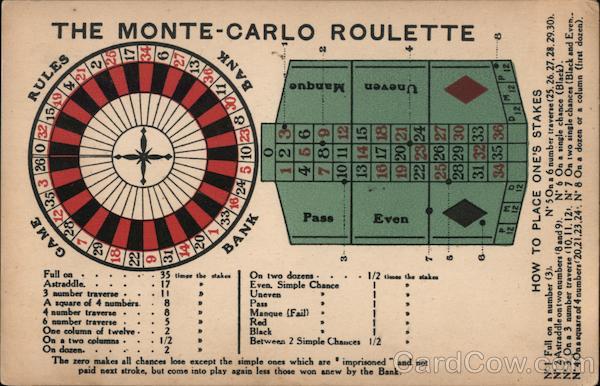

| On the 18th August 1913, the colour black came up 26 times in succession at the Monte Carlo Casino. The odds against this happening are about 67 million to 1. Players lost millions betting on red. Why we gamble like monkeys |

|

Green George

Censura

Posts : 805

Join date : 2018-10-19

Location : Kingdom of Mercia

|  Subject: Re: Fate, fortune, risk, gambling and probability. Subject: Re: Fate, fortune, risk, gambling and probability.  Thu 21 Apr 2022, 18:30 Thu 21 Apr 2022, 18:30 | |

| aiuui the faed "double headed penny" of fiction would be lss advantageous than a double tailed one. Given a choice, it seems people call "heads" about 60% of the time (I don't remember the research behind this - our headmater cited it to those of us in the Additional Maths class almost 60 years ago) |

|

Triceratops

Censura

Posts : 4377

Join date : 2012-01-05

|  Subject: Re: Fate, fortune, risk, gambling and probability. Subject: Re: Fate, fortune, risk, gambling and probability.  Fri 22 Apr 2022, 13:32 Fri 22 Apr 2022, 13:32 | |

| - Meles Meles wrote:

- In this regard introducing a random element into the ritual was often part of the practice of divination to discover the will of the god being appealed to. Rome's auspicious chickens could reveal Jupiter's will according to which direction they wandered off after being released

There is the famous story from the First Punic War, just before the naval Battle of Drepana, when the divine chickens refused to eat, not the auger the Romans were hoping for, so the fleet commander Publius Claudius Pulcher said "If they won't eat, then let them drink" and had the chickens thrown overboard. Unfortunately for the Romans, the chickens had been right and the Carthaginians won a major victory. |

|

Sponsored content

|  Subject: Re: Fate, fortune, risk, gambling and probability. Subject: Re: Fate, fortune, risk, gambling and probability.  | |

| |

|