- Caro wrote:

- Her first voyage was on 14 December 1853 sailing from Calcutta to London with ten passengers and general food/oil cargo. On the trip she collided with another ship, the Devonshire and was damaged and repaired.

The 1850s saw a signal development in marine safety. I was minded of this during Thursday evening’s ‘applause-at-twenty-hundred-hours’ when Mrs V and I heard a ship hooting its horn. It’s not something we would hear often. We’re about 7 miles inland here, so it must have been a pretty large vessel exercising a sizeable air horn. This got me to thinking about the history of ships’ horns and foghorns.

I grew up very closer to the shore (about 400 yards in fact) and on misty nights I would often hear the sombre moan of a foghorn from the Trinity House lightvessel moored about 5 miles out to sea and which marked a sandbank. My schoolfellows and I fell into 2 groups with regard to our appreciation of the foghorn. There were those who found the sound disquieting and there were those who found it comforting. I belonged to the latter group and found it easy, while lying in my bed, to go over to sleep to the rhythm of its solemn lullaby. I suppose that a mariner at sea would really want to belong to the first group and remain alarmed and alert to it and not be lulled into nodding off while on watch.

Over the last forty years, however, the number of coastal foghorns has diminished. Radar and computerised satellite navigation have been the main justifications given for the cull. Another reason would be questions about just how effective or realistic an aural warning is in the context of modern seafaring. There are also complaints about the noise itself from landward residents (i.e. the former group aforementioned) and last, but not least, cost.

(19th century lighthouse and foghorn combination at St Abb’s Head, Berwickshire, Scotland. Many foghorns were converted from steam power to oil in the 20th century.)

The first known foghorn was located on Partridge Island, Saint John, New Brunswick and began operating in 1859. The significance of Partridge Island is to be found in Saint John’s role as an important immigration point for Canada which had seen a large growth in its traffic in the 1840s largely down to emigrants fleeing the potato famine in Ireland. Saint John is situated by a natural harbour which itself is located on the relatively sheltered Bay of Fundy. Yet despite this favourable location, it is still on the east coast of Canada which is famously foggy. One need only think of the Grand Banks of Newfoundland to appreciate this. The meeting of the warm Mexican Gulf Stream and the cold Labrador Current produces bountiful fishing grounds but also treacherously foggy seas. The

Royal Charter of Saint John granted in 1785 stipulated:

‘

and that the island aforesaid called Partridge Island, also within the limits aforesaid, be at all times forever hereafter kept by the said Mayor, Recorder and Commonalty, as well as for the due use and purpose of a Lighthouse to be erected thereon, and for the keeping and maintaining a person to attend and watch the said light, for the safe navigation of the said harbour, as for a Pesthouse to be also thereon erected for the use of those who may be hereafter obliged to perform quarantine on entering the said port.’

And the year 1847 would see those quarantine facilities put to full use as a typhus epidemic struck many ports of North America, including Saint John, mainly spread aboard famine-fleeing coffin ships. At that time the problem of fog was dealt with by a variety of methods, of greater or lesser efficiency, ranging from bells to triangles and even cannons in the attempt to warn vessels about rocks and other dangers.

A resident of Saint John during that era was Robert Foulis, a Glaswegian and something of a renaissance man, who had graduated in engineering but decided to turn his hand to portrait painting to earn his living. A widower and father of a young child Catherine, Foulis encouraged his daughter in the arts purchasing a piano to help further her musical education. Yet the advent of photography meant that portrait painting now faced a strong, new competitor and so Robert was ever on the look-out for other ways to make his fortune. One dark, foggy evening as he felt his way home thru the gloom, he found himself guided up the cliff path by the sound of Catherine’s piano playing. Foulis noted how the thick air literally dampened the high notes she played (swallowing them up) but seemingly amplified the deeper tones. It’s a similar phenomenon to what happens during and immediately after a fresh snowfall. The high-pitched voices of children squealing with delight, building snowmen and throwing snowballs etc are muffled.

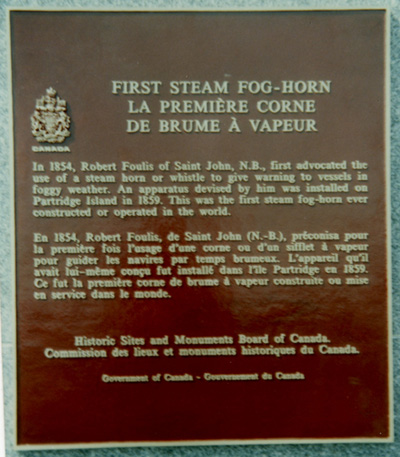

Pondering on this Robert wondered if this acoustic phenomenon could be turned to a practical use in navigation. A flurry of shipwrecks and groundings off Saint John (four in 1853 and a further three in 1854) prompted the New Brunswick coastal commission to encourage him in this endeavour. He set to work over the next few years designing a deep-tone air horn to be powered by steam. Foulis, however, naively shared his plans with fellow engineer Thomas Vernon Smith, a well-connected and business-minded individual, who then shamelessly passed the foghorn off as his own and managed to persuade the commission to buy one off him and install it on the lighthouse island where it went into service in 1859. Having failed to patent the foghorn, Robert Foulis never benefited financially from his invention although he did later get a plaque erected in his honour:

The Partridge Island foghorn was finally decommissioned in 1998 but, and as has so often been the case around the world, not without controversy. Members of the local boat club complained and petitioned the authorities (unsuccessfully) against decommissioning, while many residents of the town’s fashionable West End were in favour of the switch off. It’s a familiar story. No doubt a good many of the well-heeled denizens of Saint John were pleasant blow-ins from up-country without whose economic presence and spending power scores of coastal communities would go under, but whose estate agents had omitted to mention to them that their idyllic sea-view pads, holiday homes and weekend retreats also came complete with a non-discriminatory, 10-mile-plus-ranging, publicly-funded, super-snorer.