|

| | Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches? |    |

| | Author | Message |

|---|

Meles meles

Censura

Posts : 5120

Join date : 2011-12-30

Location : Pyrénées-Orientales, France

|  Subject: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches? Subject: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches?  Wed 04 Sep 2019, 09:01 Wed 04 Sep 2019, 09:01 | |

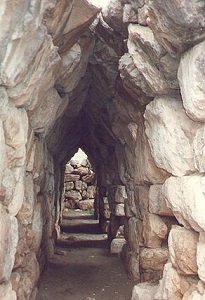

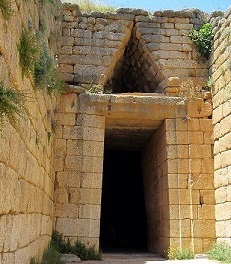

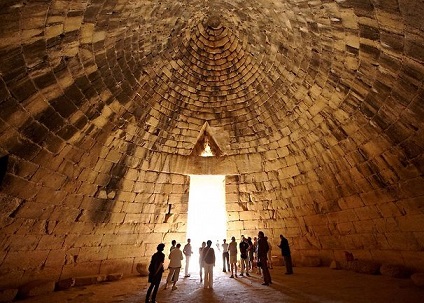

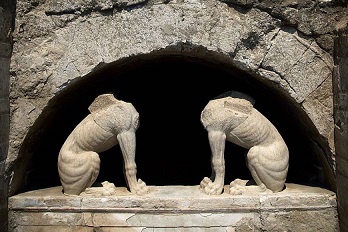

| A solid roof over one's head is one of the prime requirements of a civilised existence, but permanent roofs are heavy and the struggle to support them is as old as civilisation itself. The essential problem is how to span the gap between the walls to leave a habitable space underneath. The simplest solution is laying horizontal beams across the gap between the walls supported where necessary by vertical pillars. ie a post and lintel construction. Classical Greek architecture - as exemplified by the Parthenon in Athens (completed in 438 BCE) and numerous other magnificent buildings throughout the Hellenic world - is rightly lauded for its elegant form, balanced proportions, pleasing symmetry and quality of construction. Nevertheless for all their beauty, classical Greek temples are, almost without exception, still essentially of simple post and lintel type of construction and so structurally are really not much more sophisticated than Stonehenge. Simple wooden lintels are generally limited by the length of available timber and also by the strength and flexibility of wood, and in classical Greece timber in suitable long lengths was already in short supply and also in great demand for ship-building. According to the Bible the massive wooden roof beams for King Solomon's enormous temple in Jerusalem were 17 cubits (about 7 metres) long and these he had specially imported from Lebanon, but of necessity many buildings in classical Greece had to make do with considerably shorter lengths of timber. Stone was readily available but simple stone beams or lintels, although suitably rigid, generally have poor tensile strength and so cannot in practice be used to span distances of more than about 2.5 metres, otherwise they are liable to crack under their own weight.  An internal view of the Parthenon.  Close-up of the outer peristyle of the Parthenon. The central lintel in this image is cracked across (and repaired with a modern metal clamp) but it cannot fall as it is wedged by the heavy blocks on either side, but this would not be the case if the cracked block was on the end. The lintels of the peristyle are actually all composed of three separate blocks laid side-by-side (just about visible in this picture) in part to allow for a certain amount of cracking as well as being easier to handle during construction. That is not to say that Greek buildings were necessarily small: the Parthenon's floor plan is bigger than many medieval cathedrals, while nearby at the foot of the Acropolis, Hadrian's temple of Olympian Zeus (a 2nd century Roman construction but in the same Greek style), at 108 by 52 metres, would fill most of Trafalgar Square. But to cover such an area with a roof did require the interior to be a veritable forest of closely-spaced massive columns (the columns in Hadrian's temple are each 1.9m in diameter, 17m high and spaced 5.4 m apart, leaving gaps of 3.5m between them). This mass of internal masonry was necessary to support the huge stone lintels, which in turn supported the wooden ceiling rafters, and finally on top of all that, the heavy, pitched timber-and-tile roof.  The fragmentary remains of Hadrian's enormous temple of Olympian Zeus with the acropolis and Parthenon in the background. Arches do not suffer from the severe limitations of lintels and a simple masonry arch - and its related forms; the barrel vault and the circular dome - can readily span a gap of over 60m. Moreover an arch will still support its load even when the blocks themselves are cracked or indeed if the whole structure becomes deformed through shifting of the foundations. Arches however are not generally a feature of classical Greek architecture and it appears that there is no archaeological or historical evidence of true arches in the Greek world that can be dated with certainty to a period earlier than the late fourth century BCE. However the true arch had been used extensively throughout Mesopotamia since at least 2100 BCE and it is hard to see how generations of Greek mercenaries, military engineers, merchants and other travellers had never encountered them, or at least not recognised them as a very effective way to span the gap between walls. For example ...  The brick arch entrance to the Edublalmahr Temple in ancient Ur (now in Iraq) was built c. 2100 BCE.  A brick barrel-vaulted tomb in Haft Tepe in SW Iran c. 1500 BCE. This is actually constructed using the more sophisticated inclined brick technique where successive brick layers lean against those already in place, allowing it to be built without the need for any temporary support from below while the bricks are laid in place.  The splendid Ishtar Gate to the city of Babylon, completed circa 575 BCE and now located in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin. The Greeks of Mycenae used simple stone lintels but also extensively used corbelling; that is where the successive layers of stonework project out over the layers below so that with enough height the gap is eventually bridged. Using this method they built corbelled arches, vaults and even domes :  The corbelled vaults under the walls of Tiryns, which were already very old when Homer marvelled at them. They probably date from about 1800 BCE and despite the legends were almost certainly not built with the aid of the Cyclops.  The famous Lion Gate into the city of Mycenae dating from about 1500 BCE, with a post and lintel doorway and a corbelled 'arch' above the triangular bas relief, which serves to take much of the weight of the wall off the horizontal lintel.   Lintel and corbelled 'arch' doorway to the Treasury of Atreus at Mycenae - and the splendid corbelled 'beehive' dome of the interior, from 1250 BCE. The wide-angle lens for the interior photo is a bit misleading: in reality, as with all corbelled structures, the height of the roof is rather greater than the width of the enclosed space. The true arch seems to have been first used in Greece when the barrel-vaulted tomb was introduced in Macedonia (in the late fourth century BCE) and it is certainly plausible to see this as being a direct consequence of military engineers and architects returning from Alexander the Great's campaigns in Mesopotamia. But did it really just need a few suitably-qualified militarty engineers and architects returning to Greece with memories of what they had seen and for the first time truely understood, from when they marched in triumph into Babylon through the arch of the Ishtar Gate.  Barrel-vaulted tomb at Amphiopolis, northern Greece, currently dated to the last quarter of fourth century BCE. From these first tentative usages in Macedonia, the arch did then spread throughout the Hellenic world, but it still remained a relatively minor architectural form, until the Greek states were conquered by Rome and Roman architectural styles and practices became more prevalent.  The barrel-vaulted entrance tunnel to the stadium at Nemea, circa 340 BCE.  The greatly restored west parados arch to the theatre at Philippi, Greece circa 200BCE.  All that remains of the krypte, the vaulted official entrance tunnel to the stadium at Olympia, Southern Greece, late third century BCE. I find it difficult to accept that they simply did not know about arches, especially when they had successfully been using corbelling for centuries. So why did the ancient Greeks - generally no slouches in exploiting and developing new technologies - not use arches more often? Was it due to cultural reasons? Was the 'forest' of pillars in a temple seen to be reflecting the idea of the sacred grove perhaps? Or, somewhat like the House of the Vestals in Rome which, despite being rebuilt several times in ever more lavish stone, marble, tile and brick, was still always made to resemble the (supposed) original vestals' round thatched wooden hut. Or was it due to artistic esthetic reasons? Perhaps the four-square, post and lintel temple design was seen as reflecting in its relative proportions the 'perfection' of the geometric golden ratio ... or something like that? Or maybe it was simple xenophobia? Were arches seen as too 'exotic' or too 'alien' in a similar way that separate church bell towers rarely took off in Northern Europe as they were seen as suspiciously like the minaret of a mosque; while European medieval churches themselves usually remained cruciform, or at least rectangular, in shape, as circular churches were again thought too dangerously similar to mosques or synagogues. Or was it due to simple practicality, although I find it hard to envision what these practical reasons might have been? While construction of an arch or dome usually requires a lot of wooden scaffolding, the finished thing need not contain any timber at all: there's no wood in the construction of, for example, the magnificent dome of the Pantheon in Rome. Furthermore another problem with post and lintel designs is the difficulty of extracting flawless blocks of sufficient size for the lintels, and then transporting these large and heavy stones to the construction site. But an arch or dome does not require especially long blocks of stone. For example the large dome of the Byzantine basilica of Hagia Sophia in Istambul (completed 528 CE), or that of Brunelleschi's Rennaissance masterpiece, the dome of Florence cathedral (completed in 1432), were both constructed from thousands of relatively small, easily handled, bricks. Or to cite the Pantheon in Rome once again, most of that dome uses no solid blocks at all: it was poured into place as liquid concrete. But that is another matter entirely. Or is there another reason why the Greeks, for all their 'cleverness', failed to see the great potential uses of arches and so rarely, if ever, used them?

Last edited by Meles meles on Wed 04 Sep 2019, 11:26; edited 9 times in total (Reason for editing : many pics requiring some resizing) |

|   | | nordmann

Nobiles Barbariæ

Posts : 7223

Join date : 2011-12-25

|  Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches? Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches?  Wed 04 Sep 2019, 09:34 Wed 04 Sep 2019, 09:34 | |

| It's a fascinating question - and conventional wisdom regarding the evolution of the arch doesn't adequately answer it. What they certainly lacked was concrete, or at least anything as reliable as that which the Romans could later exploit and which gave them a huge advantage in reinforcing arches. The Romans also seemed to grasp the significance of keystones very early on and quickly abandoned corballed arches such as they had inherited from the Etruscans, whose own architecture seemed to have been heavily influenced by interaction with Greeks once they started building big. But it wasn't like the Greeks didn't know about keystones, or that corballed arches just didn't cut it in elaborate architecture employing multiple spans with as few vertical supports as possible. And they also could match the later Roman constructions when they wanted to in terms of design elements and assembly - the entrance to the Stadion at Olympia (the Krypte) being a good example of pretty accurate pre-construction planning and execution by the masons. All that differentiates it from a later Roman construction is the insurance of reinforcement with cement.  What one rarely sees in Greece is a structure with combined arches, even in sites where the architect and masons obviously knew how to build stable keystone arches. I wonder was it simply a confidence thing in a country with more than its fair share of earthquakes? They had certainly made their pillar/lintel constructions pretty earthquake -proof (lots of swaying allowed before the integrity disappeared). However maybe they just shied away from multiple arched structures where the collapse of one arched element might be catastrophic for the integrity of the whole? Interesting question though .... EDIT: Just seen your pictures (they're on an insecure site) and notice we've both displayed the Krypte. Some of your other examples also show equally well how far the Greeks were prepared to go without reinforcement, or at least that's what I'm assuming was holding them back. |

|   | | Meles meles

Censura

Posts : 5120

Join date : 2011-12-30

Location : Pyrénées-Orientales, France

|  Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches? Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches?  Wed 04 Sep 2019, 10:47 Wed 04 Sep 2019, 10:47 | |

| You don't actually need concrete to reinforce an arch (as indeed your image of the krypte at Olympia clearly shows) because arches are intrinsically very stable in their own right. And remember that the method of making concrete was actually lost for centuries and so most medieval cathedrals - with all their sophisticated arches, groin vaults, fan vaults and flying buttresses, rose windows etc - were built using simple lime mortar, which never really sets (in the center of medieval cathedral walls the mortar is even today still very often slightly moist and crumbly and in texture resembles old, partly dried-out glaziers' mastic/putty). Such mortar was never intended to act as a 'glue' but rather simply as a cushioning bed between the blocks to transfer the loads uniformly down the walls and columns to the foundations. And the idea of the all-important central keystone in an arch is rather more allegoric than in reality: all the voussoirs - ie the wedge-shaped blocks of an arch - carry and transfer the load equally. Just down the road from me is the Pont du Diable spanning the river Tech at Céret in a single arch. It was supposedly built by the Devil - because only infernal cleverness could do the job - although in reality it was built between 1321 and 1341 by the good burghers of what was then, as it is now, a fairly small and relatively unimportant provincial market town (then in Aragon, now it's in France). With a masonry arch of just over 45 metres width it was at the time of its construction the widest unsupported span in the world; and it was all built by local masons and constructed using fairly roughly-hewn blocks and simple lime mortar.  But arches are remarkably robust simply because of their shape. Unlike a lintel, an arch will still support its load even when the blocks themselves are cracked, unmortared or indeed if the whole structure becomes deformed through shifting of the foundations. For example the foundations of Clare Bridge in Cambridge subsided shortly after it was completed in 1640 but while the central arch is visibly distorted the bridge itself is no danger of falling down.  PS - Re my pictures being on an insecure site - its the same one I've always used to host images: postimage.com. |

|   | | nordmann

Nobiles Barbariæ

Posts : 7223

Join date : 2011-12-25

|  Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches? Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches?  Wed 04 Sep 2019, 11:37 Wed 04 Sep 2019, 11:37 | |

| I'm sitting behind a Forticlient web filter which objects to share sites with unsigned certificates or signatures it doesn't recognise. Seems postimage.com may have a temporary problem with their cert - it happens sometimes (with Res Historica around once every three months or so).

The Roman use of Pozzuoli ash for almost everything concrete seems to have given them a confidence in varying architectural methods that pushed spatial enclosure to limits they hadn't dared attempt before, and may account for a willingness to adopt and adapt arch construction beyond that which the Greeks were ever motivated to do. However you are correct in that they often used it where in fact it wasn't really needed at all - and arch construction is a perfect example. Which to me begs a question regarding if they too had simply inherited a deep, if misplaced, distrust of the arch even as they set about sticking them everywhere to such fantastic effect after their "Concrete Revolution"?

But I share completely your incredulity that the Greeks, at least in their grander constructions, were never seemingly tempted to employ arches beyond in some very basic applications, a construction method they apparently understood perfectly in both a theoretical and physical sense so must have also included an appreciation based on hard evidence of their load bearing capabilities.

Another aspect to construction in which the Greeks lagged way behind Romans was brickwork. Beyond some rather basic sun-dried clay applications they never seemed interested in perfecting the technique further (and given a choice in their larger structures would always ditch brick in favour of cut stone, despite the huge difference in expense involved). What's even stranger is that later Roman perfections of brick manufacture were often made with grateful attribution to kiln-firing and glazing techniques learnt from Greek sources, some of which were already quite old by the time the Romans adapted them on industrial scales. |

|   | | Meles meles

Censura

Posts : 5120

Join date : 2011-12-30

Location : Pyrénées-Orientales, France

|  Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches? Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches?  Wed 04 Sep 2019, 13:03 Wed 04 Sep 2019, 13:03 | |

| Concrete is of course not the ultimate simple answer to everything. Even concrete has its limits, which includes its own weight. Roman engineers fully understood that and whilst Roman concrete arches and domes (such as the Pantheon) are stable, they are still limited by their own intrinsic weight. That is why the Pantheon has prominent square 'decorative' hollow panels built into the upper levels of the dome (to reduce the weight) and why Roman architects, such as Vitruvius (a city magistrate under Vespasian, but also a self-taught engineer) tried various techniques to reduce the density (ie weight) of concrete particularly when constructing the upper layers of arches and domes. Vitruvius advocated adding crushed pumice (a volcanic rock; it's basically a natural sponge containing trapped pores of air) into the concrete mix to reduce the density and hence the weight of the concrete in the highest levels of construction. But it was then realised that if one was using air-filled concrete to fill between bricks, then why not use hollow air-filled bricks themselves. And what better such 'bricks' than all the terracotta wine amphorae that were cheaply available and, strictly non-returnable, were all piling up over Rome and other cities and were being simply dumped for land-fill (Rome's so-called 'eighth' hill, Monte Testaccio, now about 35m high but certainly much higher in the past, is actually nearly entirely composed of used and discarded amphorae).

The obvious solution to all these piles of discarded containers was to cast them into the foundations of new buildings, but it was soon realised that all these empty vessels could equally serve as very light-weight 'bricks'. Accordingly they were soon being deliberately incorporated into new concrete structures, especially where lightness was needed (ie in the higher levels of arches, domes and other roof structures). Indeed most of the beautiful early Byzantine domed churches in and around Ravenna are actually apparently built from used, non-deposit, wine empties. |

|   | | Meles meles

Censura

Posts : 5120

Join date : 2011-12-30

Location : Pyrénées-Orientales, France

|  Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches? Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches?  Thu 05 Sep 2019, 08:10 Thu 05 Sep 2019, 08:10 | |

| - nordmann wrote:

What one rarely sees in Greece is a structure with combined arches, even in sites where the architect and masons obviously knew how to build stable keystone arches. I wonder was it simply a confidence thing in a country with more than its fair share of earthquakes? They had certainly made their pillar/lintel constructions pretty earthquake -proof (lots of swaying allowed before the integrity disappeared). However maybe they just shied away from multiple arched structures where the collapse of one arched element might be catastrophic for the integrity of the whole?

Good point. A four-square doric temple, like the Temple of Concordia at Agrigento (constructed between 450 and 430 BCE) does exude a certain solid stability. I can just imaging the horrified shock Ictinos and Callicrates (the Parthenon's principal architects) would have had if they'd ever seen a large, and apparently flimsy, Roman aqueduct such as that at Segovia in Spain (probably built around 100 CE) and looking like nothing so much as a line of dominos balanced on end and just waiting for the first one to topple over.   Although of course part of the apparent stability of Greek architecture is ironically due to the weakness of their post and lintel design. For Greek temples to have had any chance of standing the test of time (and earthquakes) they had to be built on very precisely levelled and thoroughly stabilised foundations. Arches are much more forgiving of long-term subsidence and settling of their foundations, although maybe not so much to sudden, side-to-side, earth tremors. There's also the argument that so many Greek temples, and in particular their columns, are still standing today, is because the large cylindrical blocks were not suitable to be plundered and reworked into other local buildings. A similar reasoning (that they are not ideal sources from which to plunder stone) also applies to ancient arched structures, such as the numerous still-standing Roman aquaducts. While a wall can be gradually dismantled from the top down, it is difficult and dangerous to dismantle an arch, especially so when it is structurally combined with others: once you manage to get one of the key blocks out, the whole lot will come tumbling down with it. |

|   | | Priscilla

Censura

Posts : 2772

Join date : 2012-01-16

|  Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches? Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches?  Thu 05 Sep 2019, 10:55 Thu 05 Sep 2019, 10:55 | |

| My five pennith on this topic is that function was the overriding consideration. Greek temples, agoras and so on were for external statement and less internal use where a vaulted ceiling would cover more space for a larger crowd. Rites and altars were outside only the priesthood observed obligations within the smaller enclosed place - ostensibly a box with a lid on top.

Chitonic rites - such as at Dodona - were often observed underground with vaulted tunnel routes and chambers - and as observed above the 'beehive' tomb structures were roofed and the stone laying of these meticulous as with the few keystone arches from Mycenaean remains.

With important functions, meetings and observances held outside the impact of façade made strong statement - and with a unifying sense of order gelling things together much as their language also united diverse peoples. Column drums ( the blocks used for columns) were churned out in slave quarries along with the mass production alomost of staues and pediments at places such as Olympia.

In my opinion it was little to do with cement or know how but more to do with social mores that were copied where ever Greek colonists went much as the British built tiled houses with gables and roofs in unlikely places.

I am just thinking 'people' here and neither construction skills nor material. When enclosure is needed such as the great mosques of Turkey then architects such as Sinon ( a Christian slave) resolved it in what I think as the successful blancmange mould design.Building what is needed along with current broader mindset have their place.

Last edited by Priscilla on Thu 05 Sep 2019, 10:59; edited 1 time in total (Reason for editing : odd errors) |

|   | | nordmann

Nobiles Barbariæ

Posts : 7223

Join date : 2011-12-25

|  Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches? Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches?  Thu 05 Sep 2019, 12:49 Thu 05 Sep 2019, 12:49 | |

| You might have a point about how temples were intended to be used in Greece with a lot of the associated activity happening outside the retaining walls of the structure (though some examples of these still enclosed quite impressive roofed spaces within them). However temples are by no means the only large constructions enclosing sizeable spaces. Each city for example also had a bouleuterion, a building where all the important activity certainly happened inside rather than outside, the older one in Athens (two were built) known to have accommodated five hundred councillors in Solon's government, presumably along with all the bureaucrats, attendants and other functionaries present when councils were in session. The roof was supported by five substantial pillars within the space, something that would have impeded the conduct of the chamber to some extent and which one would have presumed could better have been resolved through use of arch construction, had the Greeks decided to use that method. But they didn't.

Another well preserved large bouleuterion in Prien, modern day Turkey, also solved the roof support issue with one gigantic pillar right in the middle of the debating chamber which would have supported four stone lintels in cross formation meeting at its top. Again this impediment to the conduct of the council was obviously tolerated rather than considered an ideal architectural solution, though again a more fitting solution as devised by Romans meeting similar challenges would have been vaulted or arched structures supported by the retaining walls. In Glanum, modern day St Remy in France, one can actually see where both solutions were indeed used, three great pillars supporting the roof when it was built as the bouleuterion by the original Greek settlers, and then these replaced by a vaulted ceiling when it was later redeveloped by the Romans as their local curia, who presumably did not see a need to suffer such intrusive obstructions to council business when a perfectly feasible alternative existed. |

|   | | Priscilla

Censura

Posts : 2772

Join date : 2012-01-16

|  Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches? Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches?  Thu 05 Sep 2019, 15:37 Thu 05 Sep 2019, 15:37 | |

| Post Solon, meetings had fewer and were more open - the crowd had a say and a vote; as for instance when Aristedes was put into exile by public pot-shard vote ( with one when asked by the current media of the times muttered that they heard his name mentioned too often.) Aristedes was of course back quickly when things got tough and the Persians fancied another bout.

My point being that in that democracy there were no walls...……… oh Lord where am I taking this?

Moving on then... quickly….. in Glanum the first Geeks out of Massalia may have built but they were sooon tossed out by the local tribes because of introduction of different cult figure to the revered shrine of The Good Mothers. Later Greeks made a council meeting place which did not infringe on local devotions higher up the complex where the sacred grotto is. Romans would have used the foundations of that because many tribals were instrument in local government with representatives in Rome some from this area too, (hree of the Attribates) - and Gauls were not into arches, either. Roman design in the round, as it were, is extent in the rest of the Province. Glanum remained tribal in most respects with Roman respect..... but the Roman conquest of Gaul below Glanum is so sadly shown in statuary there with a Gaul killing his wife before capitulating to the sword himself. Interestingly, the freeze of that Roman arch is of oak leaves, sacred to local druidic connections.

As to the Greek style, they were not adverse to things circular.... the circular tholos at Delphi being a dream of a place it seems that within a universal style that pleased them no one saw need to experiment. Early Roman attempts to copy it..... the Temple to the Discori, for instance was a bit of a mean, ill=proportioned mess. Greeks liked the mathematical precision and proportion to please the eye and intellect - the Romans eventually found it for themselves with arches - early ones are not as prepossessing in proportion as the later best...…. I know less about Etruscans - and Roman building town lay out grew from their foundations..... I have a thought that their tombs were often arched?) And Greek roots were Minoan - no arches..... and their roots from the Med countries, no arches. Perhaps the roots have it. (Not Jo Root who is making a mess of cricket captaincy and why I am at this.)

All this is a bit off the top of my head and my own rooted memory so be free to challenge,

Last edited by Priscilla on Thu 05 Sep 2019, 15:43; edited 2 times in total (Reason for editing : trimming) |

|   | | PaulRyckier

Censura

Posts : 4902

Join date : 2012-01-01

Location : Belgium

|  Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches? Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches?  Thu 05 Sep 2019, 22:22 Thu 05 Sep 2019, 22:22 | |

| - Priscilla wrote:

- My five pennith on this topic is that function was the overriding consideration. Greek temples, agoras and so on were for external statement and less internal use where a vaulted ceiling would cover more space for a larger crowd. Rites and altars were outside only the priesthood observed obligations within the smaller enclosed place - ostensibly a box with a lid on top.

Chitonic rites - such as at Dodona - were often observed underground with vaulted tunnel routes and chambers - and as observed above the 'beehive' tomb structures were roofed and the stone laying of these meticulous as with the few keystone arches from Mycenaean remains.

With important functions, meetings and observances held outside the impact of façade made strong statement - and with a unifying sense of order gelling things together much as their language also united diverse peoples. Column drums ( the blocks used for columns) were churned out in slave quarries along with the mass production alomost of staues and pediments at places such as Olympia.

In my opinion it was little to do with cement or know how but more to do with social mores that were copied where ever Greek colonists went much as the British built tiled houses with gables and roofs in unlikely places.

I am just thinking 'people' here and neither construction skills nor material. When enclosure is needed such as the great mosques of Turkey then architects such as Sinon ( a Christian slave) resolved it in what I think as the successful blancmange mould design.Building what is needed along with current broader mindset have their place. Priscilla, although I had in depth discussions in the past about the comparison of Roman vaults, arches with the medieval vaults, arches, ogives and I am very interested in this high level discussion, I can't find from my meager knowledge an answer to MM's question either. " When enclosure is needed such as the great mosques of Turkey then architects such as Sinon ( a Christian slave) resolved it in what I think as the successful blancmange mould design." I did some research for blancmange architecture and of course found all baking forms and all that...Is this a name from your own?...meaning this:  Some examples from India too? Kind regards from Paul. |

|   | | Priscilla

Censura

Posts : 2772

Join date : 2012-01-16

|  Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches? Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches?  Thu 05 Sep 2019, 23:10 Thu 05 Sep 2019, 23:10 | |

| yes, blancmange moulds is my own idea - but surely others must have thought the same.

The history of architecture in the sub continent is a whole new bag...… suffice it to say the very best was at the height if the liberal Mogul period. When austere Aurangzeb ruled the balance and proportion was lost in mean design - his Pearl Mosque is not a patch on some of the others. But that is best in another thread, however, the mindset at the time in any period reflects in grand design. The Greeks liked order. The city states had differing political views, rites, calendars, coinage and much law, what they all shared was a language and a pantheon of deities and in these there was consistency which is revealed in architecture. I ought say that many thoughts I express in this thread are my own and sometimes based on my many years of book research. …. and as you well know I never use links. Non of which means I am right, either - but that is what this site is also about...… interesting argument not only ref source of others' stuff - tho of course that is invaluable too if the nub of it is presented and not just indicated.... Nord, Temps and MM are so very good at that. |

|   | | nordmann

Nobiles Barbariæ

Posts : 7223

Join date : 2011-12-25

|  Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches? Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches?  Fri 06 Sep 2019, 07:56 Fri 06 Sep 2019, 07:56 | |

| - Priscilla wrote:

- My point being that in that democracy there were no walls...……… oh Lord where am I taking this?

Your guess is as good as mine - I'm really not sure where you're going with this at all. Many of the walls you mention in fact still exist and are substantial walls at that - bouleuteria still exist in pretty good states of preservation in over twenty five locations around the Mediterranean, and except for where we know the Romans re-purposed the building as a curia, they all have sound walls, substantial pillars in inconvenient locations when it comes to debating chamber functionality, and a distinct absence of arches (which is more or less both my point and MM's regarding the main topic of this thread). It is also wise to remember that the principal purpose of bouleteria, as with curia (simply a Roman word for practically the same function), was not a parliament in the modern sense, pre- or post-Solon, but more akin to a modern town hall, an aspect to civic administration that largely went unchanged through many centuries of changing political landscape. It was here that budgets were approved for projects discussed and agreed upon, where local taxes were set, collected (and often stored and guarded), and where matters of law - including certain criminal proceedings - were adjudicated, cases attended and heard, and where special assemblies were convened in times of perceived crisis. They also doubled as audience chambers when and if a person of greater authority required to address city leaders in person. In addition they operated as commercial centres, a mixture of stock exchanges and commodity trading halls of the modern era, so even in times of relative quiet on the civic administration front they were convenient for assembly of large numbers of people engaged in activities best conducted in relative privacy and comfort, so in fact of all extant Greek civic structures they are the one which, we know, would most consistently have accommodated large assemblies over centuries, no matter in which city they were built or whether or not the style of administration varied according to local considerations, such as cities operating as stand alone colonies or integrated occasionally into more complex confederations in Greece itself. So, while many of the democratic functions took place in the open air, in both Greek as well as Roman times, there was still a consistent requirement to have an all-weather year-round enclosed area for some of that system's more important political and economic functions to be performed in which those responsible could convene. And all seemingly without a single arch ... |

|   | | Priscilla

Censura

Posts : 2772

Join date : 2012-01-16

|  Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches? Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches?  Fri 06 Sep 2019, 08:22 Fri 06 Sep 2019, 08:22 | |

| Yes, of course there were walled enclosures for the admin - tho on reflection, the lighting therein I know nothing about. In truth of that aspect I have never given thought -and of course it can get parky in winter. Delphi resolved that by closing down for the winter and gave over the shrine to the Dionysians in whose wild rites, one assumes, neither pain nor cold was felt. |

|   | | nordmann

Nobiles Barbariæ

Posts : 7223

Join date : 2011-12-25

|  Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches? Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches?  Fri 06 Sep 2019, 08:43 Fri 06 Sep 2019, 08:43 | |

| Not wasting a space so laboriously and expensively constructed was a feature of city society. The original bouleuterion in Athens, when they downsized the required administrative forum from 500 to 300 people and built a cosier version to accommodate the new council, then went into several centuries more service having been divided up internally into the city archive, a temple to the Mother of the Gods, and at least fifteen housing units.

Windows were indeed a problem - the old bouleuterion, again largely because arches had not been employed, could only afford to have very small apertures, and only on two sides of the rectangular structure (and unsurprisingly these were incorporated into the domestic units constructed later within the building complex as the traditional apartment configuration of windowless exteriors and light admitted from interior juxtaposition to a courtyard could not be replicated). The newer one however, still without arches, got around the problem with a very expensive colonnade incorporated into the exterior wall which allowed shorter, stronger lintels and pretty decent apertures beneath each of these. Being a semi-circular building this meant light being admitted from almost all angles as the day progressed. They also nearly solved the intrusive pillar problem when it came to roof support, though only by positioning the four internal columns with two of them slightly offset to the rear of the auditorium centre (allowing most people to observe centre stage at any time) and the other two towards the rear of the banked seating area opposite (so that only when the chamber was well and truly packed with people would some have to sit behind this obstruction). |

|   | | PaulRyckier

Censura

Posts : 4902

Join date : 2012-01-01

Location : Belgium

|  Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches? Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches?  Fri 06 Sep 2019, 22:19 Fri 06 Sep 2019, 22:19 | |

| MM, " I find it difficult to accept that they simply did not know about arches, especially when they had successfully been using corbelling for centuries. So why did the ancient Greeks - generally no slouches in exploiting and developing new technologies - not use arches more often? Was it due to cultural reasons? Was the 'forest' of pillars in a temple seen to be reflecting the idea of the sacred grove perhaps? Or, somewhat like the House of the Vestals in Rome which, despite being rebuilt several times in ever more lavish stone, marble, tile and brick, was still always made to resemble the (supposed) original vestals' round thatched wooden hut. Or was it due to artistic esthetic reasons? Perhaps the four-square, post and lintel temple design was seen as reflecting in its relative proportions the 'perfection' of the geometric golden ratio ... or something like that?"And perhaps was Priscilla right in her guess:"And Greek roots were Minoan - no arches..... and their roots from the Med countries, no arches. Perhaps the roots have it. "MM, I have access to Jstor but it takes some trouble to do it via the university of the grandson...but if you are interested?...https://www.jstor.org/stable/503797?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

And especially this link: https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/s00004-006-0018-6.pdf"However, the Greeks’ reticence to use the arch and the vault cannot be explained by a lack of technical knowledge or skill. The primary factor was cultural. Similar to the Egyptians, the Greeks established a formal language for their architecture at a very early date and never deviated from its rules. Their architecture was of a trabeated type, composed of columns and beams, originally of timber and later translated into stone. Every element and detail of the Classical canon of architecture that the Greeks used in their monumental temples constructed of stone, such as the Parthenon, has a direct correlation to a timber component in their archaic domestic buildings. It was for cultural reasons that the Greeks chose not to use any structural system other than a trabeated system in their major civic and religious buildings. Their urban form, the polis, was the basis of Greek identity and defined a group as a distinct racial entity with an unbroken historical and mythic connection to the origins of their civilization. Likewise, their ancestral architectural form was the megaron, a small dwelling composed of a more or less cubic interior volume, with a colonnaded porch, both protected by a single gable roof. This was the archetypal building from which the Greeks derived the designs for all of their civic and religious structures. Even their grandest and most elaborate buildings were variations on the theme of the simple megaron. The Greek temple was foremost a symbol of the sanctuary, or shelter for a cult deity, a deity that protected and perpetuated the identity of a people. As a symbol for an immutable principle, its form could not change. Therefore, the entire architectural project of the Greek canon, extending over a millennium, was to only make incremental refinements to an established model. Furthermore, monumental Greek architecture was to be contemplated as sculpture in brilliant sunlight and in relation to its surrounding landscape; it was not dedicated to enclosing interior space. Therefore, the Greeks lacked an incentive to experiment with structural systems such as the arch, vault or dome that would have expanded or elaborated" MM, and the Greeks saw it also as a estetic (spelling? Dutch:esthetisch. French: esthétique) eye catcher. I made here on the board a thread about the bullding of the Parthenon, with the colums deformed from the bottom to the top, so that the eye would see the colums parallel to each other, while if they were of the same thickness on their whole length, the eye wouldn't them see as parallel. Kind regards from Paul. |

|   | | Priscilla

Censura

Posts : 2772

Join date : 2012-01-16

|  Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches? Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches?  Fri 06 Sep 2019, 23:40 Fri 06 Sep 2019, 23:40 | |

| Surely Romans developed arch architecture because it was expedient to do so - as in their impressive aqueducts and circus amphitheatres, Greeks knew all about maths involved and their semi circular theatres built for sound projection but saw no need of arches. Huge unsupported domes are quite a new development because there was a need for them in modern mosques...… they are cool within, for one thing.

I am just toying with thought here - it is always interesting to try to understand why a peoples did what they did...….cf the building long huts and circular ones. |

|   | | nordmann

Nobiles Barbariæ

Posts : 7223

Join date : 2011-12-25

|  Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches? Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches?  Sat 07 Sep 2019, 09:16 Sat 07 Sep 2019, 09:16 | |

| Hanlon's article is interesting, Paul. Thanks for the link. He makes two statements within it which are both correct, though for some reason he chooses not to link them. One, that the Greeks for a thousand years or so never really experimented much once they had hit upon a dependable method of supporting large structures using cut stone, is certainly true and automatically includes a failure to experiment therefore with arch construction. Secondly, he cites their reticence to employ bricks and the poor quality of Greek brickwork that has survived. This is also true. But then a third thing he says, and presents without any attempt to explain, is that the Greeks were certainly aware from contact with Eastern cultures not only how to make good arches but also how to make them using better bricks than the sun-dried variety they commonly used. I actually think this reticence to industrialise brickwork or take the technique further is probably key to understanding therefore why a disinterest in arches also occurred within dominant architectural styles in any culture, including the Greek. I've been looking at soil distribution maps throughout Greece and Anatolia and what strikes one immediately is the almost complete absence of vertisols in the entire region. These are soil groups that contain very high clay or loamy content and are by far the best brick material as the sintering process (chemical bonding of the active components with the silty content to make a strong cohesive mass) requires less heat to achieve. In other words sun-drying alone is sufficient to create a very strong brick. If you compare this distribution with that which pertains in areas of great alluvial deposit, flood plains, and areas with more regular intervals between saturation and de-saturation, then you can see immediately just how lacking the Greeks were in obtaining this material when compared with other areas, such as almost the whole of the Mesopotamian fertile zone, or even the plains of North Italy for that matter. To get around this deficiency the solution is to use soil with less clay content but fired to a higher temperature, but even then a clay content below 50% is pretty useless and further processes are required to achieve consistency of materials in the right proportions (ie. suddenly it becomes much more labour intensive an operation). If you download the map linked below you can see that even when it came to these lesser quality materials the Greeks didn't have access to very much at all within their own cultural area, or at least the land area in which their culture originated and thrived most (the soils with the deepest purple/red being indicative of such clay content). So, even if they understood the theory (and we know they did), they simply did not have any economical method of obtaining the resources required, or at least certainly not on the larger industrial scale that has to be employed once one has to artificially recreate the sun-drying of high clay content soil using vast quantities of inferior material ("extrusion" being a principal element of the process in which the inferior material is industrially removed to a point where a good enough ratio to allow sintering to occur remains). Those who did develop and use bricks on industrial scales seemed to have started out with an ample supply of the "good stuff", enough certainly to encourage experimentation using the material as a load bearing element of design. Then, once they had incorporated a dependency on this architectural style in their culture, the same people had access to enough second grade material, along with a huge financial incentive, to then concentrate on refining kiln firing processes and expanding the industry in terms of labour to meet their own demands. The Greeks had none of this at home, and their expansion abroad in terms of government and area, even when it included access to loamy soils that might have kick-started this cultural development, was never one best suited to the level of exploitation of local labour and material required. Maybe, with an expansion model more on Roman lines, and given a little more time, they might have got there. But otherwise they seemed resigned to operating within functional parameters set by both their geographical location and geopolitical model of federation and colonisation, a model that wasn't especially conducive to either cooperation or coercion enough to exploit resources at the levels required. Had Alexander's conquests retained even a little homogeneity for a period long enough, for example, maybe this might have been such a catalyst for change. However Alexander was by far an exception to the usual Greek expansion model and, with such a cultural norm established, then the incentive just wasn't there to invest effort or expense enough to make them into an overly experimental society when it came to architecture, especially since they had long ago arrived at a style and method that worked more than reasonably well anyway. In fact given their otherwise fantastic record in both absorbing new knowledge from without and experimenting just for the fun of it in almost every other respect, then I am even more convinced that the root of the matter when it comes to both bricks and arches boils down to access to material. In their place, and in the time they were at their most powerful and influential as a dominant culture, the elements required to start an architectural revolution based on innovation using materials to hand just didn't exist. Here's a link to the soil map - it takes ages to download on my machine, but if you can manage it it's interesting. Greece soil distribution |

|   | | Meles meles

Censura

Posts : 5120

Join date : 2011-12-30

Location : Pyrénées-Orientales, France

|  Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches? Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches?  Sat 07 Sep 2019, 10:59 Sat 07 Sep 2019, 10:59 | |

| And further to your comments about firing bricks ... Greece - at least the southern more lowland valleys and coastal bits of Attica, Boetia, Arcadia and Thessaly, where the best soil/clays for brick-making seem to be - was already critically short of timber, whether for general building construction, ship-building or just domestic cooking, and so probably couldn't have sustained a large, fuel-hungry, brick-making industry. |

|   | | Priscilla

Censura

Posts : 2772

Join date : 2012-01-16

|  Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches? Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches?  Sat 07 Sep 2019, 11:27 Sat 07 Sep 2019, 11:27 | |

| On the other hand some rock appears to be easy to chip into keystone and arch building shape. I saw this in 18th Cent Raj houses in the subcontinent. When being demolished for high rises the sandsstone arches used quite extensively for shaded verandahs and doorways was left till last to be more carefully removed for reuse. Marble obviously chips away quite easily (well for some, in my art training days all the rocks I used needed muscle....and talent).

You think material and I think mindset i.e. that they liked the linear design, it conformed and brought unity throughout their home and colonial expansion and the proportions pleased the eye and agreed with the setting -often on raised ground. Making bricks needs fuel and that the Greeks did not have with huge forests to hand. Of course Athens did not grow until after the 2nd Persian war before that it was all happening elsewhere - in Asia Minor in particular and colonies from the Black Sea to Massalia - which after the Phoenicians was developed by colonists from Phocis … the 'Seal' island off the Eastern Med Asia Minor coast. Greek colonists built columned temples all over long before Athens had a gush of building in the same style. And before that their city must have been of wood to have been burned down before darius could get his hands on it. Where is ID when we need her. This is only from my memory bank which in age is overdrawn you might well say. I reckon their earliest stuff was in wood - no arches and then copied into stone. Gulp. … another Aunt Sally opportunity. Why do I do it! |

|   | | Priscilla

Censura

Posts : 2772

Join date : 2012-01-16

|  Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches? Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches?  Sat 07 Sep 2019, 11:28 Sat 07 Sep 2019, 11:28 | |

| I posted to find MM had the same thoughts.... strewth! |

|   | | PaulRyckier

Censura

Posts : 4902

Join date : 2012-01-01

Location : Belgium

|  Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches? Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches?  Sat 07 Sep 2019, 22:10 Sat 07 Sep 2019, 22:10 | |

| nordmann, I think it was this sentence in the Hanlon text, which sparked your comments? "The arch and the vault had been used in Western Asia for many centuries prior to the Greeks arrival, but these examples were composed of brick, a material in which the Greeks showed little interest [Lawrence 1983, 170]. " But then when I read it this morning I wanted already say that the Greeks didn't need bricks, if the wanted to build arches. They could it do with limestone, which was available overthere. I saw I think even blue stone cut in the documentary about the Guédelon project. Constructing a medieval castle with the comtemporaneous methods. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N5gFm6_1FkMAns yes Priscilla seems to have the same opinion; " On the other hand some rock appears to be easy to chip into keystone and arch building shape. I saw this in 18th Cent Raj houses in the subcontinent. When being demolished for high rises the sandsstone arches used quite extensively for shaded verandahs and doorways was left till last to be more carefully removed for reuse. Marble obviously chips away quite easily (well for some, in my art training days all the rocks I used needed muscle....and talent).You think material and I think mindset i.e. that they liked the linear design, it conformed and brought unity throughout their home and colonial expansion and the proportions pleased the eye and agreed with the setting -often on raised ground. Making bricks needs fuel and that the Greeks did not have with huge forests to hand."I think Hanlon has a point, when he said the Greeks stuck to their old style of building for traditional? religious? reasons.Digged a bit everywhere, not exactly to get confirmation of that theory, but more to seek if the materials available, as limestone, marble were easy to cut, saw...https://www.ancieanalysis_of_important_themes_in_greek_architec/ntgreece.com/essay/v/http://learnmore.ancienttemple.gr/constructing-the-temple/?lang=en[size=50]T[/size] he early Archaic temples were of rather makeshift construction. The walls were of mud bricks and only the lower sections (socle) were built of small stones. The first columns were wooden.The roof, always gabled, was also of timber. The tiles were of fired clay (terracotta), as were the various decorative elements that completed or protected the timber or mud-brick constructions.

From 620 BC, however, the use of ashlar blocks in Greek temple architecture began. During the sixth century BC this became generalized, with the resultant abandonment of timber and mud brick as building materials, at least for the most important monuments.It has been ascertained that the architectural features established in the wooden temples of the previous period were transferred to stone, in both orders. Morphological analysis, particularly of the Doric order, shows that the entire building was close to its timber precursors and models. Even details were reproduced in stone, such as the nails used to join the wooden members together. Thus, in Greek temples we have, as it were, a ‘petrified timber structure’. This conservatism of the Greek architects is interpreted as confidence in forms that had acquired aesthetic value after many years of development.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ashlar"Thus, in Greek temples we have, as it were, a "petrified timber structure. This conservatism of Greek architects is interpreted as confidence in forms that had acquired aesthetic value after many years of development. Kind regards from Paul. |

|   | | nordmann

Nobiles Barbariæ

Posts : 7223

Join date : 2011-12-25

|  Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches? Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches?  Sat 07 Sep 2019, 22:48 Sat 07 Sep 2019, 22:48 | |

| Then you're missing my point about cheaply produced strong bricks in abundance facilitating the initial experimentation and refinement required to produce ambitious arched construction as a norm within any culture's monumental or large scale construction projects. Quarried stone, however abundant stone might be, has never been an economically viable medium available enough to cultures, even those ingenious, organised and willing enough, to accommodate a desire or inclination to explore architectural options available beyond those established methods that already have proven to work satisfactorily. To develop such techniques to a point that they are adopted as principal architectural styles they must first have been introduced organically into a community, refined and adapted through trial and error by a large number of people leaving enough proofs of concept standing from which others might then learn, and then gradually reach a point where sufficient demand for their use exists to make even expensive adaptation and execution a viable option.

Hanlon and others, when regarding Greek architecture in hindsight and with the benefit of direct comparison to what others may have done in different climes and in later ages, and possibly with inordinate concentration on temples to the detriment of consideration of other engineering requirements they also faced structurally during the same period, seem to be good at stating what is completely obvious (the Greeks didn't use good bricks or arches) but maybe not so good at deducing why this might have been so.

If you can convince me that quarried limestone (or quarried any stone) matched brick made cheaply from abundant sources elsewhere in terms of economy and general availability, and therefore could have facilitated that critical level of application in sufficient instances within the Greek culture to emulate what developed elsewhere regarding evolving methods of structure and design, then I'll agree with you that they seem to have missed a trick. But I'm more prepared to take the simple evidence of what we know happened in all these places, the materials each had to play with, and the relative costs to each culture of the construction they engaged in using those resources most readily available (all construction, not just that on a grand scale) as sufficient reason to assume that it was very much more practical circumstances that dictated the aesthetic involved and not the other way round. |

|   | | Priscilla

Censura

Posts : 2772

Join date : 2012-01-16

|  Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches? Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches?  Sat 07 Sep 2019, 23:34 Sat 07 Sep 2019, 23:34 | |

| With nonstop potoi. amphora and such made at an industrial level, bricks may have been one use too much - but an abundance of slaves chipping out temple drums for columns - and rock blocks that could be quarried with some precision and with a view to grand design, permanence and uniformity I still have no quarrel with that notion - a sort of Lego V Meccano situation. And Paul mentioned wooden beginnings ancient wooden tholos with wooden columns have ben found - or rather strong indications of them in northern Thrace. And columns relate to trees - much as the processional naves of churches and similar in many ancient sites in Europe. And a random thought, Greeks liked or rather used the angular rather than curve in the formation of their alphabet - which I have seen argued was derived from Phoenician script. Whatever - I am so pleased they stuck with what they liked so much of more recent grand statement architecture still impresses - and we can do bricks far easier and at a fraction of the cost. So. |

|   | | nordmann

Nobiles Barbariæ

Posts : 7223

Join date : 2011-12-25

|  Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches? Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches?  Sun 08 Sep 2019, 10:03 Sun 08 Sep 2019, 10:03 | |

| Greek industry is not in question, and like many other societies of the period utilised clay-firing efficiently to create amphora and other storage and culinary vessels. But other than the fact that clay was utilised the similarity with brick production required for superstructure construction ends. The raw material required, the level of industry required, and the investment of application and commitment to its continuation is very different indeed. A broken amphora and a failing superstructure are both potential calamities for those affected, but the scale of each calamity is markedly different.

The aesthetic question, especially if it is to be presented as a primary reason why any society would persist in one architectural style over another, still has to answer the "chicken and egg" aspect to its adoption. Egyptian column construction (another society with inferior bricks and avoidance of arch development by the way) is frequently said to have been inspired by the aesthetic of standing papyrus reeds, and the fact may not have been lost at all on early Egyptian architects who may indeed have emulated the aesthetic intentionally, but it is also true that their column use in large constructions represented the most logical and efficient use of the materials they had to hand.

The writing analogy defeats me in terms of relevance - the Greeks also produced a rather beautiful cursive version of their alphabet characters when writing with inks. The angular characters favoured when cutting into stone strike me as a logical option, and in fact it wasn't until well into the Roman period that significant use of semi-cursive symbols started appearing in stone inscriptions. Carving a curve is much more difficult than a straight line and even the Egyptians, two millennia prior to the Romans, knew how to achieve the effect but reserved its use for very expensive application requiring huge levels of social investment. When the Romans worked out ways to produce this effect industrially using cheaper methods it too then became a dominant aesthetic meme, in fact one that we still employ today and which we associate with high aesthetic ideals as a font suitable for socially important visual statements. Which again reflects the dilemma of the "chicken and the egg" when assessing aesthetics versus resource usage in the development of any widely adopted style. |

|   | | Green George

Censura

Posts : 805

Join date : 2018-10-19

Location : Kingdom of Mercia

|  Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches? Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches?  Sun 08 Sep 2019, 17:15 Sun 08 Sep 2019, 17:15 | |

| Part of the next posting.

Last edited by Green George on Sun 08 Sep 2019, 20:56; edited 1 time in total |

|   | | Green George

Censura

Posts : 805

Join date : 2018-10-19

Location : Kingdom of Mercia

|  Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches? Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches?  Sun 08 Sep 2019, 17:28 Sun 08 Sep 2019, 17:28 | |

| Columns don't aways relate to trees, of course. They can also be serpents.   The Great Siege: Malta 1565 In this, Bradford claims that Maltese limestone (from other reading I suspect specifically the globigerina limestone) can be cut with a knife when newly extracted, and subsequently hardens on exposure to the air. |

|   | | Priscilla

Censura

Posts : 2772

Join date : 2012-01-16

|  Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches? Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches?  Sun 08 Sep 2019, 18:22 Sun 08 Sep 2019, 18:22 | |

| By the time the Greeks got to writing with ink most of their grand design stuff was in place - enduring too, thank goodness. Indus valley cities - and I do mean cities - of circa 1800 BC were all of brick - there being little stone that did not need lugging a far leap, are now mounds of brick. Over the centuries much of that was removed to build local villages. Uniform in size and used for everything including lining of well - which now stand as chimneys following much digging about them no bricks were used for arches. Stone blocks were used for roads, lining and covering drainage ways and bigger stuff for quays and docks. The brick buildings also had waterproofing - bitumen or resin I cannot recall. And waterproofing in places with rainy seasons is important.

As for fuel to fire all that pottery wood was needed for shipping also. Most of the timer for that would come from further afield.... the Black Sea eastern seaboard forest because it can be carried part prepared or towed to ship yards which are by the sea....cf the East coast of England. A ship building tradition since HenryV111 and probably earlier only closed late in the 20th Cent and the water front timber yards importing seaborne wood until then to make furniture was for a time the main industry of a small town near to my home. The transport of wood to fuel brick furnaces would not have been economic - not with chunks of rocks to hand. Mud bricks in hot fry lands of course were for small dwellings and according to the Bible slaves made those in Egypt. |

|   | | PaulRyckier

Censura

Posts : 4902

Join date : 2012-01-01

Location : Belgium

|  Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches? Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches?  Mon 09 Sep 2019, 00:29 Mon 09 Sep 2019, 00:29 | |

| - nordmann wrote:

- If you can convince me that quarried limestone (or quarried any stone) matched brick made cheaply from abundant sources elsewhere in terms of economy and general availability, and therefore could have facilitated that critical level of application in sufficient instances within the Greek culture to emulate what developed elsewhere regarding evolving methods of structure and design, then I'll agree with you that they seem to have missed a trick. But I'm more prepared to take the simple evidence of what we know happened in all these places, the materials each had to play with, and the relative costs to each culture of the construction they engaged in using those resources most readily available (all construction, not just that on a grand scale) as sufficient reason to assume that it was very much more practical circumstances that dictated the aesthetic involved and not the other way round.

nordmann, there you can have a point. I spent my evening by searching again to my hobbyhorse about the reintroduction of the brick in Northern and Central Europe in the 12th century... And yes it were just these countries, which had perhaps the neccessary clay layers, especially at the coast as in the Flemish Plain along the Channel. And they had the wood. First letting the clay bricks drying in the sun and later fire them in a kiln. (in the childhood i had a closed kiln as neighbour and an open one some hundreds meter further). There is still no firm evidence that the Cisterians reintroduced the bricks and the kilns again after some 4 centuries of wood and natural stone constructions. I will make a new thread about it, as there is news about more sophisticated methods as luminisence to date bricks if they are reused Roman bricks or new ones from new kilns. I put here the entries to later use them in the new thread: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/85086.pdfhttps://www.researchgate.net/publication/296865148_Brick_Production_and_Brick_Building_in_Medieval_Flandershttps://orbi.uliege.be/handle/2268/190364That said nordmann and I think it was that too that you wanted to emphasize (?), first you need the material to make bricks, but that is not enough, you need also the knowledge to do the work and have the organisation to do it on some industrial scale? And it is there, that, although there is controversy about some intermediary brick making as in Saxon England, only the Cisterians started kilns on an industrial scale and organised the whole processus from clay to brick and only then that in my opinion the real start came from the Brick Gothic https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brick_GothicFor instance: Even the Westhoek region in the very north of France, situated between Belgium and the Strait of Dover participates in northern Brick Gothic, with a high density of specific buildings. For example, there is an amazing similarity between the belfry of Dunkerque (FR) and the tower of St Mary's church in Gdańsk. and the  Church of Our Lady in Bruges and that of Saint Salvator also in Bruges. What I meant, although the clay and the wood was available for making bricks, the technology and the will had to be present to start this new cultural design? And yes where these materials were not present in abondance, they still stuck to the natural and other material to build their cathedrals? https://www.abelard.org/france/stone-in-church-and-cathedral-construction.phpnordmann, or was it this that you wanted to explain? Kind regards from Paul. |

|   | | nordmann

Nobiles Barbariæ

Posts : 7223

Join date : 2011-12-25

|  Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches? Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches?  Mon 09 Sep 2019, 08:05 Mon 09 Sep 2019, 08:05 | |

| Well, you're addressing the challenge society faced when it already had access to the knowledge required not only to use brick but also how to use it in adventurously practical ways, but was lacking either access to the materials involved or the social infrastructure required to exploit that knowledge on a grand scale. Until a means of re-introducing this market demand could be found then the industry, the expertise required to exploit the market, and by inference local development of this expertise could not be re-introduced either.

Ireland actually represents a very good example of this - even more profoundly than mainland Europe in that there is a common but incorrect belief that Ireland had always lacked both the knowledge and the incentive to acquire this knowledge or to generate a brick-making industry right up to Norman times or later, and it is certainly true that pre-Norman society did not use bricks as standard building material. The belief then is that when brick-making was introduced it was therefore completely new, as were the market forces of supply and demand to sustain this industry as defined by Norman society. The picture is therefore of a local community happily sitting in brick-making ignorance and requiring a huge social upheaval and imposition of standards, methods and styles by an invading elite before it even grasped the concept of bricks at all.

However there are two instances which contradict this perception and which show that Ireland in fact was in the same boat as much of the rest of Europe in the first millennium CE but just to a more pronounced degree - one being a Roman villa/trading post/military base complex that has been excavated in North County Dublin in recent years. Despite contradicting the notion that "the Romans" never reached Hibernia, the excavation has revealed a settled community existing for at least a century and probably longer in which all the building techniques one would normally associate with that period of Roman architecture is evident, including some very well made bricks. The clay used was of a good quality for firing, but was not sourced locally, the best guess being that it came from near the Boyne Valley, about 50km distant. This suggests an infrastructure and local economy which hitherto had been presumed to be alien to Ireland at the time, the know-how for both probably also introduced by the same Romans, which at least briefly provided the market, means and incentive to run a brick-making industry. Small by European standards elsewhere under Roman occupation, but nevertheless there.

The second instance is even more intriguing, in that one could be forgiven for assuming (as many historians did) that this nascent industry died a death once whatever the Romans were up to in the area also died out. However in the thousand years between then and the Normans there is more than enough evidence at this stage to indicate that the industry continued, this time completely within the ambit of religious orders, who not only employed well made bricks but obviously sponsored brief flourishing of that industry in various localities at different times. In other words a limited market continued to exist that exploited knowledge first introduced by the Romans, but which never reached a size that led to imposition of whatever architectural styles the material facilitated into secular society. This correlates completely with what we know about Gaelic society's attitude to local settlement - the economy did not depend on villages and towns, or even great masonry projects for the elites, so that wider market simply could never exist. However in fits and starts the techniques survived, and innovations developed locally and elsewhere were utilised by that limited market throughout this time.

What I was addressing however wasn't so much how, when and to what extent brick-making and construction with this material existed within any society, but to what extent it has to exist before it kick-starts architectural innovation to a point where structures like arches not only become a prominent feature of a local architectural style, but also a point where local manufacturers and builders can unilaterally develop and refine these techniques further. This became easier to achieve as time went on and knowledge was disseminated throughout the European continent with some rapidity, but when one goes right back to those early European societies embarking on the continent's first great experiments in solid structures on a huge scale then even more of these factors have to coalesce in one spot before a common dependency on the product generates a market large enough to sustain both the industrial process and the innovation process this engenders. Greece, I reckon, definitely falls into this category, and one result of this therefore was a lack of access to dependable bricks on the scale required to experiment and develop radically new architectural concepts compared to those which already prevailed using more accessible materials and which worked reasonably well for the purpose intended.

And, as Priscilla has noted several times, when this existing style was done well it looked well too, so good in fact that it still persists as a pleasing aesthetic to this day, even though the necessities that engendered it have long been met using more advanced and often more practical means. Greece wouldn't be the last society either to doggedly stick with a predominant architectural style even when feasible alternatives presented themselves for consideration. In fact I reckon that right up to the very recent modern age this was the norm rather than the exception within European society (and probably elsewhere too - I am less familiar with the development of architectural styles and their adoption in Asia, for example, but I imagine the same economic, material and social parameters applied wherever communal societies developed). |

|   | | PaulRyckier

Censura

Posts : 4902

Join date : 2012-01-01

Location : Belgium

|  Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches? Subject: Re: Why did ancient greek architects rarely use arches?  Mon 09 Sep 2019, 22:40 Mon 09 Sep 2019, 22:40 | |

| nordmann, " What I was addressing however wasn't so much how, when and to what extent brick-making and construction with this material existed within any society, but to what extent it has to exist before it kick-starts architectural innovation to a point where structures like arches not only become a prominent feature of a local architectural style, but also a point where local manufacturers and builders can unilaterally develop and refine these techniques further. This became easier to achieve as time went on and knowledge was disseminated throughout the European continent with some rapidity, but when one goes right back to those early European societies embarking on the continent's first great experiments in solid structures on a huge scale then even more of these factors have to coalesce in one spot before a common dependency on the product generates a market large enough to sustain both the industrial process and the innovation process this engenders. Greece, I reckon, definitely falls into this category, and one result of this therefore was a lack of access to dependable bricks on the scale required to experiment and develop radically new architectural concepts compared to those which already prevailed using more accessible materials and which worked reasonably well for the purpose intended."Now I understand you better. The key sentence is:"but to what extent it has to exist before it kick-starts architectural innovation to a point where structures like arches not only become a prominent feature of a local architectural style, but also a point where local manufacturers and builders can unilaterally develop and refine these techniques further."And thanks to you I did now again the whole exercise of why the brick making, as in your words again kick started in North West Europe in the 12th and 13th century. And not the Cisterians had the key role it seems now, but rather the need of the local authorities in an expanding society as these of the reappearance of the cities, for easy building material.And yes between the Romans and this 12th century there seems to be still a local brick industry, as you mentioned about Ireland and seemingly Saxon England and also France. But not yet kick-started as you expressed it.Thanks to new methods, as luminiscence they can now accurately date the bricks and by that reconstruct the history.https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/85086.pdf